“They’re all gonna die and no-one cares.”

It’s time we talk about “Jurassic World: Fallen Kingdom.” To say that the record surrounding the film needs to be set straight is to imply that the record is merely askew. The film is a critical reject, a general audience snoozer, and, at least anecdotally, reviled by long-time fans of the “Jurassic” franchise. Amid these circumstances, it seems naïvely bold—perhaps even arrogant—to suggest that redemption can be found in reevaluation.

Buried deep under these layers of disapproval, a truth lies in wait, preserved for those foolhardy cinematic archaeologists who dare to search for it.

My friends, today we are such archaeologists.

This undertaking—this reconciliation—this revelation—cannot possibly be seen through unless we chart a course and proceed with purpose, so allow me to humbly propose that we set out to accomplish the following:

Determine what the movie is.

Discuss why the movie is bad.

Discover why the movie is great.

Setting the Stage

Where better to start our journey than from a place of good-faith? Let us eke-out one square foot of common ground between every party to this discussion with a sentiment that should be agreeable to everyone familiar with the film:

“Fallen Kingdom” is not a typical entry into the “Jurassic” franchise.

What does that mean, if anything? For our purposes, it means that it represents a significant departure from its predecessors in several clearly definable ways. The most concrete of these is its aesthetic makeup, which we’ll reduce to imagery and sound for simplicity’s sake—the movie doesn’t really feel like it belongs in this series. Its other differences include its meta-treatment of narrative and its means of communicating with viewers (these ideas are more abstract but no less essential). We’re not here to relitigate the series; we just need to agree that “Fallen Kingdom” is a little bit different.

If we may all take one more step together (including even the least generous dissenters, I hope), we might look at this outcome and attempt to diagnose intent: the movie clearly doesn’t seek to be a typical entry. In fact, a quick and thorough unmooring of viewers’ expectations would appear to be a key aim of the work. The impulse to view this splinter as a transgression is more-than-reasonable—it certainly carries with it the potential to feel greatly disorienting. What, then, does the movie have to gain by being directed in a manner that creates this dissonance?

Imagine that you are seated in the front row for a play, but the stage curtains open and unveil something else entirely. What is being revealed? Not simply a different play, but instead something that forces you to change your behavior as an active viewer.

Perhaps, and bear with me here, the curtains open up to an opera (of sorts).

“Ridiculous! An opera? With dinosaurs? A ‘Dino-Opera,’ if you will?”

We will! And, indeed, we are.

An opera, among many, many, many other things, can be an extraordinary, paradoxical exhibition of artifice. To be a tad bit reductive, an opera is constitutive of people wearing costumes, standing among inorganic sets within the limiting geometric confines of a stage, yelling quite loudly at hundreds of other people (who, as it happens, are largely delighted by all the yelling). While the display can be enthralling, it can also be immensely alienating. Dave Malloy conjures this specific sensation in his magnificent musical adaptation of Tolstoy’s “War and Peace” (put more accurately, his adaptation of a selection from), titled “Natasha, Pierre, and the Great Comet of 1812.” The production’s protagonist, Countess Natalya “Natasha” Ilyinichna Rostova, sings the following while attending an opera for the first time:

Grotesque and amazing

I cannot follow the opera

Or even listen to the music

I see painted cardboard

Queerly dressed actors

Moving and singing so strangely in the lights

So false and unnatural

I’m ashamed and amused

And everyone else seems oblivious

Yes everyone feigns delight

Natasha, clearly not immersed in the work, finds herself transfixed by its most artificial aspects, distracted from the virtues of the art form by the nature of its presentation. This reaction isn’t incorrect—no earnest reaction would be! In many senses it’s just about the truest thing she could feel in that moment. What is also true is that, when viewed from a different perspective, the characteristics of opera that she singles out as bemusing oddities turn out to be inherent to its profound power. There is no trickery or deception; its technical proficiency and craftsmanship is laid bare, but improperly calibrated expectations can give pause to even the most well-intentioned viewer.

Before expounding this, we should address one of the elephants standing so skeptically in the room: obviously “Fallen Kingdom” isn’t an “opera” in the traditional sense. However, it is certainly operatic, exuding a shameless extravagance bound to catch many an unassuming viewer completely off-guard. To refer back to an earlier point, the movie could not be much further removed from the tasteful restraint exhibited by “Jurassic Park,” which left an inconceivably lofty high-water mark for the films that followed. In this way, though, it is perhaps the most honest sequel in a series which has evidently taken no issue with venturing into the patently absurd, as it is the entry which most fully takes ownership of its deviations from the precedents enshrined by the original.

So, is the film an opera? No. The Tyrannosaurus rex doesn’t literally break into an emotional aria.

Is it operatic, and thus primed for its own classification? You bet.

“Fallen Kingdom,” or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Pulp

Like its cousins of space and soap, the Dino-Opera is henceforth notorious for its melodramatic scripting and presentation. Contemporary melodrama is an amorphous, rather vague concept whose place in the current discourse is pinned down less as a specific genre or mode and more as a “you know it when you see it” sensibility. It centers on communicating through pathos, perhaps messily but succinctly summarized as a work trying to draw emotions from its viewers by being emotional itself. You know the markers: a conspicuously leading chord progression, line delivery whose subtlety seems to be more fit for stage than screen, a pan or zoom that doesn’t risk a single wandering eye as it hones in on the visual center of a moving moment.

As it just so happens, “Fallen Kingdom” is rich with melodrama, much of which concerns its treatment of dinosaurs as characters instead of creatures, and I would argue that its most prominent instance stems much less from the actual text of the scene than from its form. Start the below clip around 1:55 and see for yourself.

Everything here is conveyed almost entirely through its textural elements. The imagery, softened by the rolling smoke, captures the tragedy of the moment as if it were painted onto the camera’s lens, while the score seems to reach out from within the fire itself, traveling the distance that our dear Brachiosaurus could not. While “Fallen Kingdom’s” script does not appear to be public record, we can imagine that the words tasked with describing this moment do considerably less work than what we’re given by the film itself; this is a common thread that we’ll see emerge again and again throughout its duration.

Along these lines, another trait commonly associated with (although certainly not inherent to) melodrama is writing that takes the “sub” out of “subtext.” This is a large part of why the label “melodramatic” seems to carry with it a backhanded connotation, and why many might consider a melodramatic work to be best viewed through a lens of ironic detachment. The idea of art embracing a viewer’s detachment as a virtue may seem fatally misguided, but sometimes it can be the only way to save a movie from itself.

Do you remember how I implied that everybody would only agree on one thing about “Jurassic World: Fallen Kingdom?” Well, it turns out that there’s something else!

“Fallen Kingdom” sports mystifyingly awful writing, and, no, I’m not about to argue that this is somehow a good thing; that would be ridiculous. I am about to argue that this somehow does a good thing, because, before condemning the film entirely, we should ask it how it feels about this particular deficiency. On one hand, it’s absolutely possible that the film could be unaware that its script is thinner than the paper on which it’s printed as it forges ahead with a self-seriousness that winds up weighing down the proceedings. (I’d argue that the original “Jurassic World” fits this description rather nicely!) Alternatively, it’s also possible that the film is much more aware of this absurdity than it initially lets on. What at first seems to be a jarring, focus-shattering weakness may ultimately prove to serve a purpose that helps to cast the entire film in the proper light.

In fact, the lackluster script manages to accomplish something fairly conducive to the work’s high-level aims (lest you forget, we are talking about a Dino-Opera). The writing, in all of its confounding badness, exerts a type of pressure on us that disrupts immersion (a cardinal sin against conventional wisdom, to be sure) and necessitates a change in our viewing approach. We can react to this pressure in one of three ways:

1. Viewers can “push back,” so to speak, and remain determined to take the movie at its literal word. This inevitably leads to frustration and disappointment, as exchanges like the following can (and absolutely will) drain from these viewers the will to proceed.

"Keep her in there, and keep the door locked."

"You want to keep her locked in?"

"That's exactly what I want."

2. Viewers can turn off the movie or leave the theater. You know what? Valid. But there’s a better way!

3. Viewers can relent and allow themselves to be pushed—to be listlessly ushered to a new headspace. As it turns out, the movie pushes you far enough away so that you can detach from the stakes established by its text and instead begin to observe the brilliance of its spectacle.

What if Natasha, instead of reeling away from the performance because of its artifice, simply leaned back and took in all of its peculiarities at once. Might the “false and unnatural” components cohere into something wholly new and baroque? Might this revelation have saved her from meeting Anatole Kuragin during the very same production and subsequently falling into a doomed love which directly leads to her ultimate, tragic refusal of Andrey Bolkonsky?

This article is ostensibly about a dinosaur movie.

Anyway, we’re now properly geared up for our return to the other feature we highlighted as being key to the film’s assertion of independence from the balance of the series: aesthetic composition, which we’ll examine through the lens and impact of its joyous technical competency.

As it turns out, the fact that something is incredibly stupid doesn’t mean that you can’t construct the ever-loving hell out of it.

Spectacular, Spectacular

Grossly manufactured in all the right ways, “Fallen Kingdom” eagerly plays to the back of the house. It’s a work meant to evoke laughter, awe, and, yes, groans; even as its narrative unfolds with an asinine temerity which makes you wonder how such an otherwise finely tuned machine could so direly malfunction, its aesthetic coherence defines the work as a resoundingly operatic triumph.

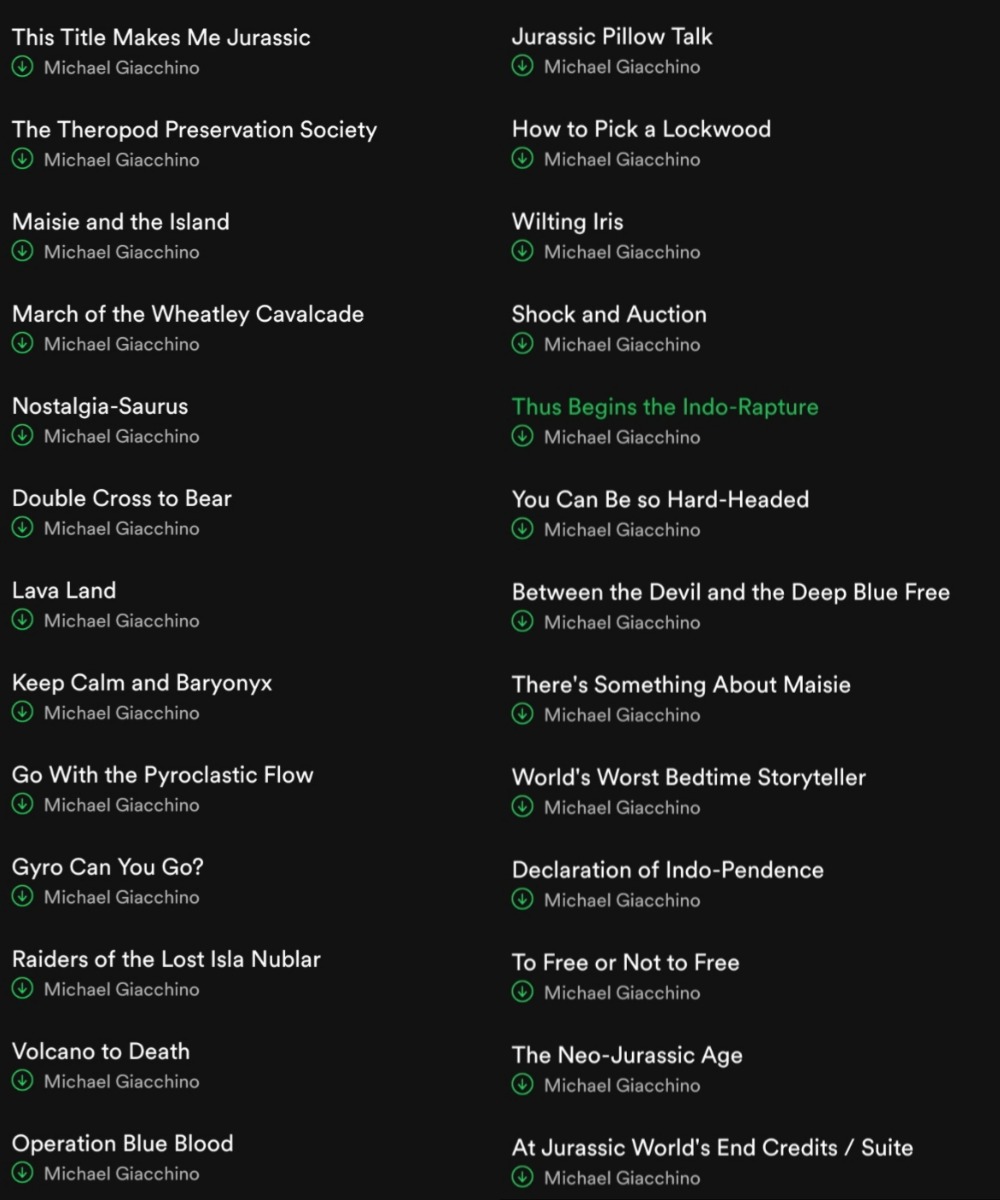

Michael Giacchino is an invaluable composer with a miraculous trait: he has this uncanny ability to follow John Williams without being lost in the legend’s shadow. The first non-Williams artist to write music for a live-action “Star Wars” film (Gareth Edwards’ “Rogue One”), his score for “Fallen Kingdom” is as bombastic a collection of tracks as you’ll find anywhere. Its intensity is ratcheted-up to absurd magnitudes, winding beloved motifs so tightly over mountainous crescendos that you’ll swear they’re about to snap with each harmonious swell. An imposing choir lends an elevated texture to the sonic booms of the bass and baritone brass, bonding and trading blows with the action onscreen.

Take, for instance, an example from the clip linked earlier in the piece (titled “Saved by Rexy”): our heroes find themselves trapped amid a stampede, and it’s all very dumb. Hiding behind a glass orb and a fallen tree, their cover is rapidly and effortlessly demolished by the oncoming dinosaurs. Giacchino, meanwhile (starting in-full at 0:57), deploys alternating minor hits that sync perfectly with each collision. It’s so on-the-nose that it effectively becomes a form of musical commentary, comedic, for sure, but played with a straight face. You can sense an exasperation in each strike, as if it’s trying to bemoan the fact that the dinosaurs can’t even align their charges with the tempo.

As a brief aside: the song titles themselves work to all-too-giddily give the game away, albeit in a much less pertinent manner. (The delightful nonsensicality of the phrase, “This Title Makes Me Jurassic,” makes it one of my personal favorites.)

All of this foists upon the film’s imagery a surface-level expectation of grandiosity and gravitas—a sort of cinematic passing of the baton—and the hand off couldn’t be much smoother. Oscar Faura’s photography is made by its audacious illumination, and the film enthusiastically accommodates, seeming to find any and every excuse to introduce dynamic, diegetic light sources.

“This auction hall is ridiculously staged, makes no logistical sense, and is immensely impractical,” you say.

“Sorry, couldn’t hear you!” Faura replies, as he noisily drills a gaudy LED grid to the bottom of the dinosaur display cage.

When viewed as a component of the Dino-Opera, the willingness to subjugate scenario-appropriate practicality to the film’s imagery is a vital asset, one that is wholly consistent with its successes elsewhere. Even beyond its portraiture which boasts a staggering sensitivity to color and composition, Faura’s camera (under J.A. Bayona’s direction) displays a profound acuity for visual adaptability and inventiveness. A darkened tunnel seeping with neon-esque hits of lava, a towering plume of smoke back-lit by fiery eruptions, and an ornate Gothic spire silhouetted against a massive moon are all images presented through a lens that seems to will the narrative into increasingly photogenic panoramas.

For one last case study, we’ll take a look at the film’s climactic showdown (featuring the “Indoraptor,” a deviously concocted new breed of dinosaur). See how architects Bayona, Faura, and Giacchino all work to present a situation which otherwise resides a stone’s-throw away from unfilmable tripe as a genre-bending showstopper (one that is still saturated with textual idiocy, of course). Watch as they wrangle the final deus ex machina into a visual moment befitting the phrase’s roots.

A Night At the Dino-Opera

Let’s be real; after all of that you’re kind of in too deep to not go and watch “Fallen Kingdom,” either again or for the first time. When you do, if you take one thing away from this insufferably overzealous exercise, just remember the following: when it feels like the movie is pushing you away, consciously decide to see where it takes you. Hopefully, when all is said and done, you’ll find yourself at just the right distance to enjoy the stupid, magnificent grandeur of it all, because it genuinely is something special.

Have a wonderful night at the Dino-Opera.

Leave a reply to Review: Tenet – Intangibles Film Cancel reply