This here? This is the edge, bruh!

The final frontier of Manifest Destiny.

Last edge of the city.

Man, two steps further, you’ll be drinking

that filthy saltwater. But we built these ships.

Dredged these canals.

In the San Francisco they never knew existed.

And now they come to build something new?

Whole blocks half in the past, half in the future.

Or should you venture into their San Francisco,

the one they pillaged for gold!

Remember your truth! In the city of facades.

Look at them look at you. Look down at you.

But we built them!

We are these homes!

Their eyes…

Their pointed brims…

We move if they move.

Our sweat soaked in the wood.

Gilded in our image.

This is our home!

Our home!

Our home.

– Preacher, from the opening monologue

It’s officially Oscar season, folks, and what better way to christen the occasion than with a prolonged discussion about one of the year’s great movies that will almost certainly be overlooked in tomorrow’s slate of nominations? I sat down with José Martinez, educator extraordinaire, to talk about Joe Talbot & Jimmie Fails’ premiere feature film, “The Last Black Man in San Francisco.”

This piece does contain plot-sensitive information (part of its structure essentially serves as a front-to-back synopsis), as it’s meant to be accessible to anybody who hasn’t seen the film. The movie is streaming now on Amazon Prime so please, please find some time to check it out.

ZD: Let’s begin with a broad view, as this piece may very-well serve to introduce some readers to the film which opened to a fairly low-key theater run on limited screens earlier this year (its widest release was to 207 theaters according to BoxOfficeMojo). What do you make of the relationship at the heart of the picture, between Jimmie and Mont?

JM: Even with little exposition, just a few anecdotes thrown around throughout the course of the movie, something about Jimmie and Mont’s relationship felt genuine. From the moment you see them skateboarding down San Francisco together, waiting for a bus, or standing in front of Jimmie’s childhood home, one can’t help but feel like these two have been inseparable for their entire lives. They feel like a dynamic duo from a “Saturday Morning Cartoon,” you can barely imagine one being around without the other. Major credit to both Jimmie Fails (Jimmie) and Jonathan Majors (Mont) for making the friendship transcend the boundaries of the narrative.

ZD: That inseparability is crucial, and I think understanding the nature of their relationship is the key to parsing the film’s perspective, as it’s crafted with a very subjective lens, one that often feels influenced by both characters. There are moments in which the two seem to live in a sort of synchrony largely informed by their understandings of San Francisco—

JM: —and grounded in their connection to Jimmie’s childhood home.

ZD: Exactly. On that note, it feels worth shedding some light on how the two men have come to see the city. Knowing that Jimmie’s old home is going to be so integral to the bulk of this discussion (as it is to the film’s narrative), maybe we should start by asking and answering the question: What is San Francisco to Mont?

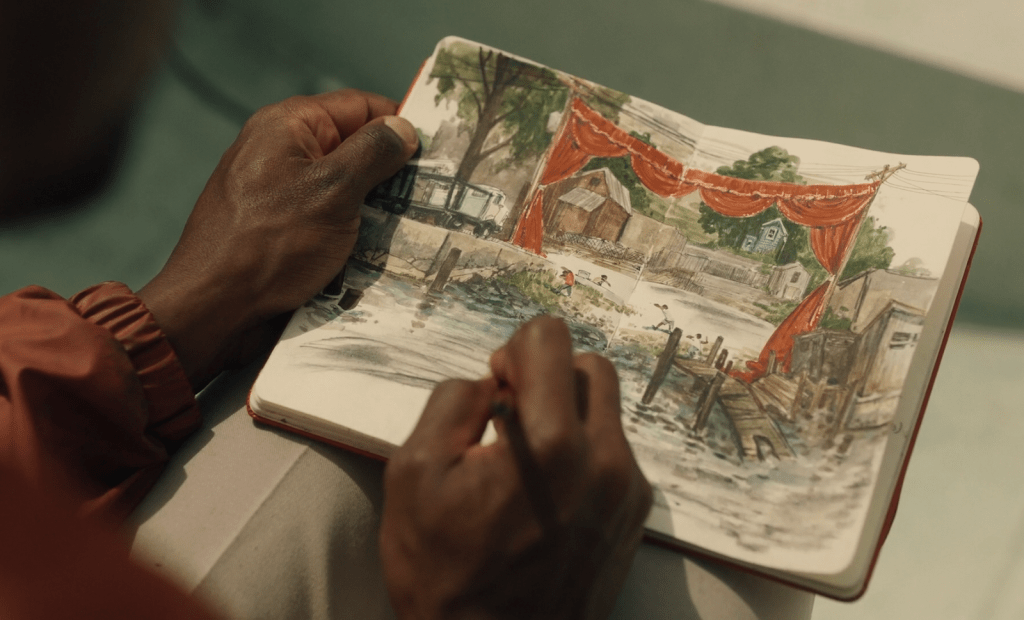

JM: To Mont, San Francisco is a play in motion; something to be observed, broken down and reinterpreted. Throughout the movie, he sketches, studies, and rehearses conversations and motifs he sees from the city, even if he doesn’t play an active role in these conversations or happenings. In what I believe is a breakout performance for him, Jonathan Majors does a fantastic job of selling Mont as this guy who is almost separated from the world around him much like a playwright is separated from his stage. In one scene in particular, Mont directly steps into a fight between four friends, three of which are ganging up on the other for being too weak to stand up for himself, and tells them that the “energy” they are harnessing is great but “not quite there yet.” He then goes on to give them advice, much like a director would, on how to better improve their performance. While a poignant breakdown of hypermasculinity in its own right, the scene does a great job of sharing with the viewer how Mont actively parses the world around him. San Francisco is a character to study and appreciate regardless of how it feels or acts towards him.

ZD: I think that the idea of Mont as a director touches on something—

JM: —it touches my heart.

ZD: Well, yes. It also brings to mind the role of the artist in trying to find and communicate truth in a relentlessly complicated world. An artist is inherently an artificer, a forger of unrealities, but their mission is to convey truth. This paradoxical nature has proved an endlessly rich vein for many an introspective work that may seek to deconstruct not only its specific medium but also, on a meta-level, its truth-seeking quest. As you said, Mont is a playwright, and—to this aim’s immeasurable benefit—he is also an avid seeker and lucid identifier of artifice. This quality at times manifests in his interpersonal relationships (as you’ve noted, he can see past the facades people construct to hide their insecurities) and as it does, he puts pen to paper and records his experiences, all the while seeking the truth behind what drives the characters that populate his life. This rings just as true in his relationship with Jimmie, as Mont sees in him a soul that won’t let him rest until he’s realized that for which he’s ached his whole life, a soul as implacable as it is genuinely motivated. The two form a kinship bonded by earnest pursuits of their passions, each complementing and supporting the other.

JM: It’s really no surprise how close Mont and Jimmie are in the movie considering how abstract their worldviews can be. Unlike many of the transplants the movie puts into focus, Jimmie feels and acts like he has a tangible interpersonal relationship with San Francisco. Jimmie believes that San Francisco is a part of him. But, before I even go into that I’ll point out again that Talbot’s directorial style and camera movements really does let the city grow as a fully fleshed character by the time the movie is over.

ZD: More than any film this year (perhaps barring Claire Denis’ “High Life,” but that’s some stellar company to keep), “The Last Black Man in San Francisco” is a deeply textural picture. Its sense of place is grounded in the intimacy of the performances, of the warmth radiating from the baritone horns in Emile Mosseri’s sumptuous score, and of Adam Newport-Berra’s photography, at once bold enough to seek out stunning compositions and sensitive enough to occupy places of quiet reflection, capturing sprawling civic vistas before lingering among dust in an attic. These textures lend an immediacy to the proceedings and help to forge a subconscious link between Mont, Jimmie, and the viewer.

JM: For Jimmie, San Francisco is more than just some place he can call his childhood home. In a very real way, the city is at the core of his own origin story and who he is as a person. At the center of this relationship is Jimmie’s love of his childhood home. While he has lived away from this classic Victorian home for many years by the time the movie starts, he still visits constantly with Mont and repairs the house even while others take residence inside (and even when they explicitly tell him to leave them be for the tenth time). Jimmie believes that this house’s beauty, and San Francisco as well, comes from its history so he does whatever he can to ensure that the house’s history is kept conscious. Unlike many of the pedestrians that the movie sometimes brings into focus, the city’s historical image is worth fighting for even as it undergoes a rapid change that threatens to break that. He constantly reminisces about, and even at one point proudly retells the story to a group of “distinguished truth seekers” taking a segway tour of the city’s Fillmore district, how the house was originally built by his own grandfather in 1946 who he refers to as the “First Black Man in San Francisco”.

Jimmie sees himself as being connected to the city intrinsically through their shared history and because of his grandfather’s grand role in its current image. He feels destined to reclaim the house under his name and restore it to its past glory, regardless of how impossible that may seem. To Jimmie, San Francisco is worth fighting for because, in a way, he is San Francisco. He’s a self-proclaimed patriot fighting for what San Fran truly stands for and what it “really” is. And like any good patriot, he isn’t willing to see the house nor the city conform and change into something that he thinks goes against its core values—which is why he brings Mont on his journey.

ZD: Mont becomes engrossed by Jimmie’s vision, captivated by the framing in which he structures his life. The two of them share an idealistic compatibility which only serves to strengthen their bond; just as Mont sees the surrounding world as a director observes a play, so too does Jimmie have the clear, bold understanding of his life’s story, aware that he himself functions as both penman and leading man. Jimmie exhibits a passion for reclaiming his family’s house–poetic in both its purity of motivation and place within his life’s story–and Mont in-turn draws artistic inspiration from this narrative. There’s a meta nature to their agency within the film, the two of them almost-knowingly forging a path observed by Talbot’s lens and, subsequently, the viewers.

Together they progress towards their goal, with advancements occurring inexorably through a harmonious combination of Jimmie’s relentless dedication and fortuitous happenstance. Eventually they find themselves within the walls of the house that they’d heretofore only seen from the outside. In a tender moment at the intersection of choice and inevitability, Jimmie asks Mont to pick a room in the house that would be his and only his, and Mont selects the dining room.

JM: This so perfectly encapsulates how Mont sees the world. When Jimmie tells him to choose a room to call his own he immediately looks up towards the dining room, with its beautiful ceiling mural, chandelier, and abundant natural light, and claims it as his own. What was once a dining room is reconstructed and evolved into something much more intimate; just Mont’s. With this Mont also redefines his place in the world as well. He joins in on Jimmie’s quest, and now has a new purpose to shepherd. Just after this short-lived scene, the movie cuts to Mont’s old room to juxtapose just how much bigger his role in the world became.

ZD: They become mutually invested in seeing this story through to its conclusion, and at first there’s no dissonance in their cooperation; as far as Mont can tell, Jimmie’s truth is shared with the world’s-at-large, aligned with history. However, before too long, Jimmie makes a discovery that cries out and strikes an errant tri-tone in a major soundscape: the house’s story is not what he had come to believe—his grandfather didn’t build it. Evidently, this truth is one which Jimmie at some point had learned and then unlearned, one which existed only in the recesses of his mind, repressed for the sake of a greater mythological coherence. The narrative unmooring doesn’t lead to a true falling-out between the two friends, but it does create an introspective distance fit for reflection and re-evaluation. Jimmie has to learn to view his life as separate from a greater narrative to which it had formerly felt inevitably, inextricably bound.

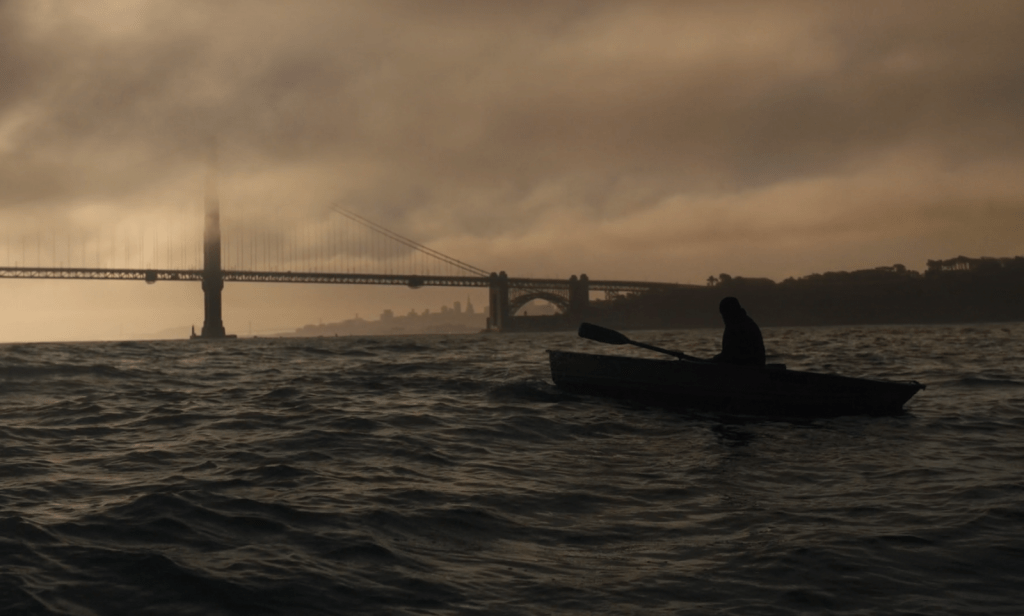

Jimmie decides to leave San Francisco—to leave Mont. The final portrait of their relationship, in brushstrokes which convey a somber buoyancy, captures the optimism inherent to Jimmie actualizing and acting on the truth of his circumstances and the tragedy of the two friends’ indefinite separation. In a sequence which deftly links metaphor and landmark, Jimmie rows away from the shore, past the Golden Gate bridge and into the unknown, while Mont stays behind, standing on the pier, looking out for his friend.

Although viewers are aware that Jimmie grapples with the question of whether to stay or go in the waning stretch of the film, what motivates his decision remains grounded in subtext. Why does Jimmie feel the need to leave, and what about this feeling makes it strong enough to overcome even the immediacy of his connection with Mont?

JM: Before we dive into this question, let us first consider the lens through which we want to answer it. From what framework should we work within? Do I dare suggest that we—

ZD: I know where you’re about to go with this and I love it. Hell, you brought this up a while back and sparked the idea for this whole piece. Bring it.

JM: —use Chesterton’s work as our basis for looking at this question? Ok let’s begin. In his most popular apologetic work, Orthodoxy, G.K. Chesterton dedicates a chapter aptly named “The Flag of the World” in which he questions what kind of person is best fit to change the world for the better. He does this throughout the chapter by looking at what kind of citizen would be best for the betterment of a city, which makes it even easier to draw from for Jimmie’s sake.

Chesterton begins by asking if a pessimist is a good candidate for his “citizenship award” but then deconstructs that notion almost immediately. The problem here mainly being that a pessimist hates the city they live in too much. While they feel strongly about injustices or inconveniences around them and aren’t afraid to point them out, these feelings are almost solely motivated by hatred. So while the pessimist is blessed with the ability to see these problems instead of glazing over them with rose tinted glasses, they’re stunted by their own motivations. Their vices lie within their demotivating tendencies, their failure to see potential, and their failure to dream. A pessimist would never be able to change their own city for the better because they chastise but they do not love what they chastise — they don’t have a primary loyalty to the city itself.

On the other hand, an optimist is plagued by his own issue. Unlike the pessimist, the optimist believes that the world around them is worth fighting for. They see beauty wherever they look and love the city enough to act upon any injustices they may see. However, this earnest love and patriotism for their city is rooted in a misguided understanding of everything around them. For while the optimist will be ready to proclaim some of the great things their city has to provide, they’ll never acknowledge anything that goes against the picture of the city they’ve painted themselves. They’ll forever palliate any negative aspects, and will even go as far as to create myths and fables to cover them up, all in the name of fighting for the integrity of what they “think” their city is really all about. And while myths and fables can motivate positive change, as long as the person knows that it’s a story created to communicate some lesson or moral, the optimist instead uses them to escape real history and loses themselves in it. They cannot fight for the betterment of the city because they do not understand what the city actually needs.

Instead of these two, Chesterton posits that a different kind of person is necessary to change society as we know it. Someone who somehow “hates it enough to change it, and yet [loves] it enough to think it worth changing” and is both a pessimist and an optimist at the same time. In his words: “Someone who is ready to smash the whole universe for the sake of itself.”

With these definitions now fresh in our minds, I think we can begin to look at Jimmie’s actual place within San Francisco and why he needed to leave. Like you said before, some unspoken turmoil hangs over Jimmie’s head at the end of the movie that “forces” him to leave. Whatever these festering thoughts are must have also been strong enough to outweigh his friendship with Mont, something even Jimmie realizes at the end when he calls him his best friend. Whatever affected this sense of urgency and abrupt exit must have then been external to their friendship. What do you think it could have been?

ZD: Ultimately, this decision was as inevitable as anything he’d envisioned for his life before this turn. He came to realize that his life was much more than that of a character within an established narrative, and so the question naturally becomes what to make of this newly discovered agency. Artifice, while providing an invaluable vocabulary with which an artist can communicate truths, is an impossible bedrock upon which to build a life; sooner or later the cracks in the foundation must give. Jimmie’s family narrative is what had formerly buttressed his position as Chesterton’s optimist, as its story dealt in broader, more absolute terms, and most any action taken on its basis would likewise betray a lack of nuance. “This is the way things were, are, and must be,” can function only until “the way things were” is thrown into question.

JM: And once this all comes crumbling down and the realities of the past and what “things were” are reintroduced, Jimmie can no longer see himself as the protagonist of this story. The narrative which fatefully bound him to the conflict between the gentrification of San Francisco and the hallowed ground that was once his childhood home has withered away. When Mont urges Jimmie to see the house for what is truly is, away from his own optimistic definition and artificial construct, he can no longer fight this battle. Really, more than anything else, Jimmie is now a stranger in a world he thought he once knew. Why would he stay in a San Francisco so different from the one he cherished for so many years?

ZD: Jimmie is left with two key considerations, the first of which being, “What does San Francisco have left for him?” The readily apparent answer is that Mont is still there, but that notion itself doesn’t get at the entirety of the picture. Mont is living his own life, caring for his blind, elderly father, and pursuing his own creative impulses.

JM: Although we only get subtle hints to this, it’s safe to assume that Jimmie has no place with his family either. His relationship with his father has been strained to the point of no return. In their final scene together Jimmie confronts his father about the truth, but his father bitterly storms off unwilling to entertain a world where his father wasn’t a hero. Jimmie is then left alone in rediscovering this world of his. And his mother? All we know about their relationship is that Jimmie glorifies her and looks up to her like some ethereal being. Whatever their relationship once was is no longer within reach, and she hasn’t played an active role in Jimmie’s life since his adolescence. Likely another reason why holding on to this myth of his was so important.

ZD: Undoubtedly so. Jimmie realizes that, amid all of this, staying simply for the proximity of a friendship, even one as strong as theirs, would be to deny himself a similar type of personal fulfillment, one that can only be sought when you’ve come to understand yourself and what drives you. This leads directly to the second of Jimmie’s considerations, even more vital than the first: “Who am I?”

The end of “The Last Black Man in San Francisco” marks the true beginning of Jimmie’s odyssey; as he departs the city so too does he cast aside any illusion of certainty he once held regarding his future. His relationship with the city and what it represents has been changed forever, but in what ways remains to be seen. He’s no longer the entrenched optimist, but nor is he among the pessimists, the likes of which he rebukes late in the film for so flippantly dismissing the city and its virtues before even trying to understand it beyond the most superficial glance. Where he stands with respect to Chesterton’s hero is still undetermined, but for now his sights are set inward on self-discovery.

JM: While the movie never answers what this journey of self-discovery is going to look like or what the future holds for him, I do believe that Jimmie will come back to San Francisco one day. When all is said and done, no one is in a better place to stand for “San Francisco” in the way that Chesterton calls for. What we are left with as the credits roll is a man who now needs space and distance to internalize all of the changes the city has gone through and who must come to terms with what is good and true.

Even as his myth comes crumbling down, his love and optimism for the city remains unceasing; in his heart Jimmie still realizes that San Francisco will always be a part of him. At first it might seem excessive to believe that Jimmie needed to take a step backwards once Mont “smashes” the world that he once thought to be true, but one shouldn’t fault him for wanting to see the city from the outside for once and not as part of a greater narrative. Be it with flowers in his hair or as Chesterton’s hero, one day Jimmie will come back to Mont and San Francisco. Within him lies the power to speak the city’s true spirit for all to hear.

Leave a comment