“Como yo lo voy a saber? Solo estoy mirando.”

“How would I know? I’m only watching.”

The new Coen brothers’ film, “The Ballad of Buster Scruggs,” opened on Netflix this weekend. Coming off of “Hail, Caesar!” (2016) and “Inside Llewyn Davis” (2013), the duo appears to be focused on finding inventive ways to discuss the artistic process, whether through narrative and character development or immersion-bending structural decisions. Does their latest, a collection of shorter Western genre stories, continue this trend, or have the directors set their sights elsewhere?

I sat down with José Martinez—middle school teacher, student of philosophy and theology, and good pal—to hash out our thoughts on their latest offering.

ZD:

So where do you start with a movie that features a duet with an angel, a suit of armor made entirely from wash pans, and an owl staring daggers into beloved singer and songwriter Tom Waits? Let’s begin by being as specific as we can within our own gut reactions: What was your favorite vignette? Give us a sense of what it’s all about for those who haven’t seen the movie.

JM:

I’m close to saying “The Mortal Remains,” but I wanted just a little bit more from its closing scene.

Ultimately, I’d say it was “All Gold Canyon.” In this vignette we follow the life of a prospector (Tom Waits) who’s discovered an uninhabited Canyon, which he suspects is rich with gold. Here, unbothered by anything but owls and deer, the prospector spends all of his days searching for an elusive gold vein he refers to as “Mr. Pocket”.

Like many of the other vignettes, the Coen brothers ask the viewer to ponder life in the American Frontier, and, in this case, romanticize the allure of adventure and riches being just a stone’s throw away. Compared to the rest of the vignettes, I felt like this story gave the viewer enough room to let their imagination run free with embellished ideals of American grandeur. Because of all that, the stark contrast and reversal of tone at the end of the story was the movies’ high-point to me. Its deconstruction of Western motifs felt more profound and thoughtful than some others.

ZD:

Loved “All Gold Canyon.” Literally anything with Tom Waits is okay in my book.

I can’t stop thinking about “Mortal Remains” (which, as the movie’s finale, is about as far from closing fireworks as you can get). Featuring a vaguely ethereal stagecoach ride in which nothing is known until it’s spoken, it has the classic Coen trait of being completely and overtly about the total work’s themes, which could risk feeling a bit on the nose if the preceding five stories weren’t as varied as they are. It also features an existentially electrifying performance by Jonjo O’Neill (as the Englishman), who casts a chilling wave of coherence over the entire picture with one brief monologue.

You mention that we were maybe left wanting a bit towards its end, and I don’t necessarily disagree, but for me that emptiness is more a virtue than a vice, especially given the way that it parallels the sequence’s own rumination on uncertainty in the afterlife. (Aside: that final shot of the hotel’s interior is absolutely peak Coen.)

Considering that uncomfortable ambiguity, let’s get into it: what do you make of the different ways that the Coens approached the concept of death in the film, and which did you find most striking?

JM:

The Coens open the film with the titular vignette, “The Ballad of Buster Scruggs,” and initially I thought that was an odd choice. Thinking about it now, though, it really did set the tone for how they were planning on engaging with death, a central theme to each story. Tim Blake Nelson’s deadpan monologues to the audience before his violent outbursts seemed so needless (and absolutely hilarious), but after his final speech something became clear to me: the overarching fear of and presence of death in the film served to compliment its homage to classic Westerns and their overarching ideologies. Buster Scruggs stood for the ideals that every cowboy stood for, but because of it, death followed and inevitably caught up with him. In that same way, death hung over every one of the other stories in the anthology. While they all tackled different Americana virtues, the Coen brothers made a point to show us that virtue can evolve into vice.

I think that in a very basic sense most habits or actions can be turned, or perverted, into a virtue or a vice; it all just depends on how you plan on directing that action. When talking about how someone views themselves someone can either be humble or they could be filled with pride. The same goes for gluttony and temperance, greed and charity, anger and mercy, etc. In either virtue or vice, the basic form starts off in that same grey area, but it eventually gets pushed it into one of those two categories. With that in mind, the Coen brothers pick apart the virtues fetishized in Western movies. In Buster Scruggs you get a guy who exemplifies the ideal form of a cowboy, trying to play things by the rules until someone stands in his way. Of course, those very same virtues (in this case his lone wolf Cowboy machismo) end up being his downfall. In “The Gal Who Got Rattled,” the protagonist, Alice (Zoe Kazan), is the archetypal damsel of the Wild West. She does what she believes she is supposed to and makes sure to do everything she does with tender love and care. That lack of autonomy leads to what might be the film’s most gut wrenching ending. Death hangs its hat by the door of all of these vignettes as a consequence of the western motifs these characters hold dear.

ZD:

That rings true for me, and it introduces a more allegorical aspect to the stories than I initially saw. The suggestion that death follows excess is intertwined fairly explicitly with the cardinal sins, and that’s certainly no reach here, especially given the film’s setting amid turbulence on the Western Frontier. In Alice’s case in particular, the “vice” is not her own; it belongs to the society that fosters such expectations. This also plays well with the Coens proudly immutable representations of the director as God (perhaps most vividly realized in “A Serious Man” and “Hail, Caesar!”). If their characters have agency, then it can be tough to discern independently from the nihilistic trials forged in the Coens’ writers’ room.

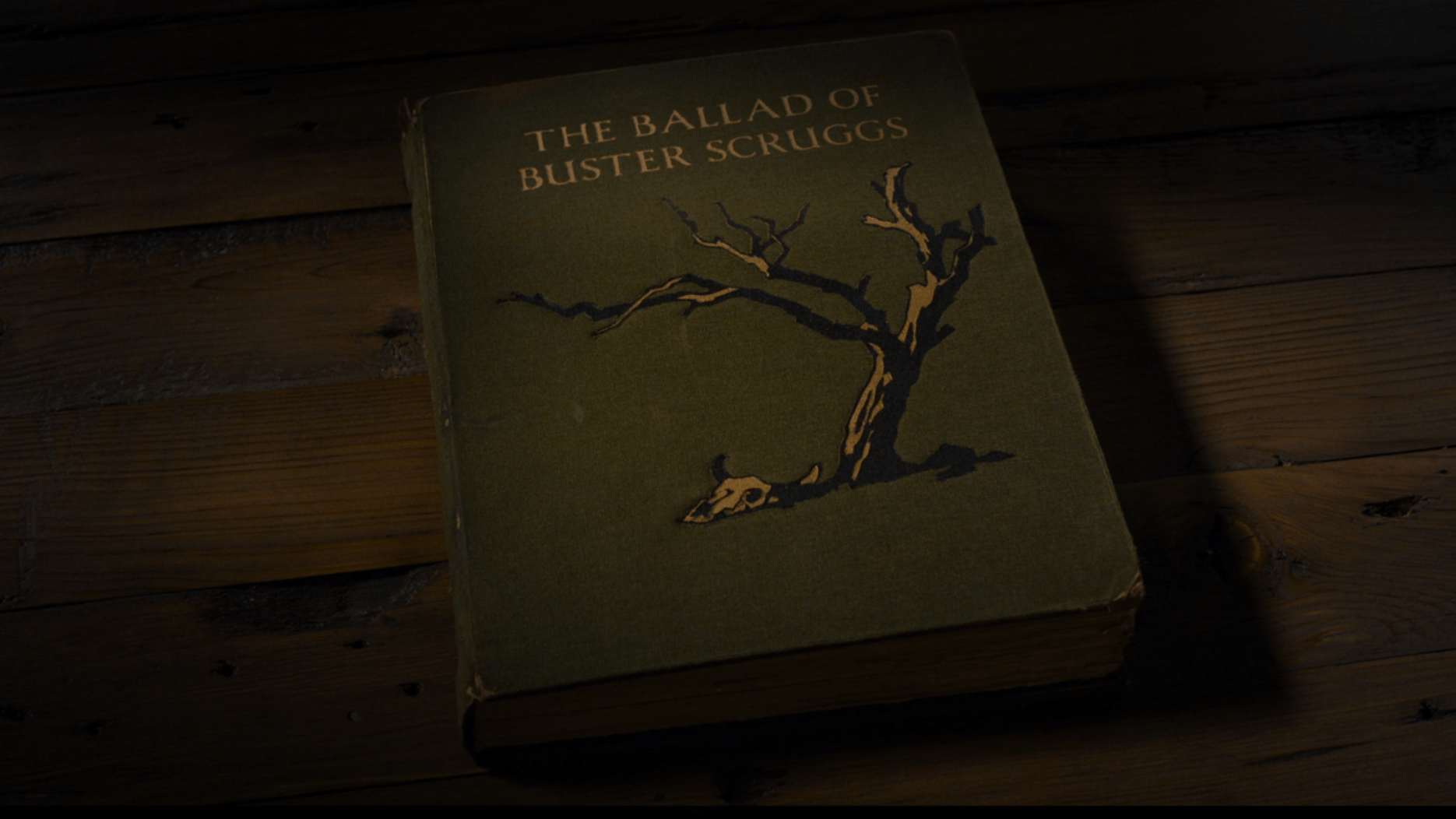

Given that high-concept, allegorical angle, I want to get into something that I find particularly compelling within “The Ballad of Buster Scruggs,” and that’s the framing device around the vignettes. It’s a large storybook that very deliberately invokes the written word and painting in-between the primarily cinematic stories, and its value to the film goes far above and beyond its utility as a static partition. When we talked through our initial reactions to the movie you had some really interesting thoughts with regard to this sort of holistic presentation of the stories.

JM:

Just from an aesthetic standpoint, I thought the inclusion of the book and paintings made the movie seem more grounded, if that makes sense. What I thought was also interesting about this intermingling was how it seemed to provide context for these stories to come in together. It gave all of them a few more layers to chew on, and, in my opinion, it allowed the Coen brothers to not only deconstruct western cinema but also mull over the role death and mortality plays in our own lives.

There’s a (relatively) recent school of Catholic philosophy referred to as Thomistic Personalism. For millennia, Catholic philosophers and theologians wrote about “man” in an objective sense. I.e. “Man is a creature with an intrinsic, and God given, sense of self-worth and dignity.” In this way, they’d essentially lay out definitions and then proceed to craft arguments for why their definitions are true. This newer school of philosophy instead focused on taking a step back and pondering what it meant to be a person from the subjective sense. Sure, we have these objective definitions, but how does a person experience life as the subject of their own reality? The way that conversation is framed in this school of philosophy, is through the lens of community.

The way that man, as far as these philosophers are concerned, comes to realize their sense of worth and dignity is through communicative acts. It is through our relationships to others, organizations, sports teams, religion, etc. that we create a framework to understand ourselves and the world around us. While a definition of what it means to be man might exist, how we come to actualize this is entirely up to the relationships that we make. Art, and how it provides commentary on itself and other forms of art, works in the same way. By itself art may have its value, but its full magnitude cannot be deduced in just a vacuum. Instead, by creating a movement or community of artworks and ideals we can create a framework in which proper context can be delivered.

ZD:

That’s a pretty striking parallel, and at its core seems to lie the idea that life contextualizes art which contextualizes art which informs life (which contextualizes art, and so on). With this movie, the Coens don’t simply want to talk about “death;” they want to talk about the way that death impacts art and how that art affects our lives. They’ll show viewers a painting, but, impressive though it may be, we aren’t yet aware of its context. We can appreciate it for its aesthetic beauty and infer meaning from the still alone, and though these are by no means insignificant things, they also are not everything. The page is then literally turned to the beginning of a new chapter, and a story plays out on-screen, a story that soon ends as its final page manifests and can be read as prose. Here’s an excerpt from the ending of “Meal Ticket,” the film’s third chapter:

“Its view was of receding road, wagon spooling up turns in front to present them unspooling for the bird’s contemplation behind. And so they traveled, forward, onward, toward dramas the outlines of which blurred in the dozing of the man, and were by the chicken dimly surmised.”

When we see the painting again (upon re-watching the film, naturally), we have a much less bounded understanding of its origins and inspiration: it’s based on a frame of the movie, which depicts a narrative from the storybook, which gleaned inspiration from reality.

JM:

The way that the vignettes persisted through different mediums made them that much more interesting. To go along what you just said, I think the creation of this storybook also gave the movie a framework that enhanced its repetition. By the second or third story, the viewer is expecting to see this book open up again and is waiting expectantly for a new image to tease an unknown tale. It’s a connective tissue that makes the stories seem more connected than a series of Black Mirror episodes, for example. It felt like we were supposed to view them all as smaller pieces of the whole.

By creating an anthology, instead of just crafting a singular narrative, the Coen brothers allow viewers to pull from more context to arrive at the work’s overarching themes. The main advantage to how “The Ballad of Buster Scruggs” is organized is that it can deliver a commentary on different aspects of Western aspirations while, in a larger way, showing how those very same aspirations were perverted and ultimately rendered futile in death.

Like you said, in this movie death follows excess. It’s a cautionary tale about the role we allow mortality to play in our own lives. Death can slowly creep its way in to flip any narrative and destroy our ideas of human triumph. That subconscious ticking clock makes even the strongest men run for answers. Yee-haw.

ZD:

Yee-haw, indeed.

I feel that some people will watch this work and dismiss it as a bout of quirky nihilism, a film ripped from their 90’s oeuvre, but I get the sense that it actually seems to care about its characters. It condemns the tides that sweep people into amorality, but it doesn’t deny the humanity of the people. When Buster Scruggs kills a man in a duel, viewers are promptly reminded that one man’s victory is, for another, the end of everything.

… before immediately being prompted to ask, “Or is it?”

By the time you have art which stands as a commentary on death, such as this movie (and such as the paintings and writings within the movie), you’re seeing something crystallized—something artificialized toward the end of realizing the abstract. What, in this case, are the Coens trying to crystallize? What are they trying to wring from abstraction? As with many questions surrounding this movie, we turn to “The Mortal Remains” for an answer:

Englishman: “I must say… it’s always interesting watching them… as they try to make sense of it, as they pass to that other place… I do like looking into their eyes as they try to make sense of it.”

Trapper: “Try to make sense of what?”

Englishman: “All of it.”

Lady: “And do they ever… succeed?

To paraphrase the Englishman’s response to that final question:

How would we know?

We’re only watching.

Leave a comment