“It’s like I’m having the most beautiful dream and the most terrible nightmare all at once.”

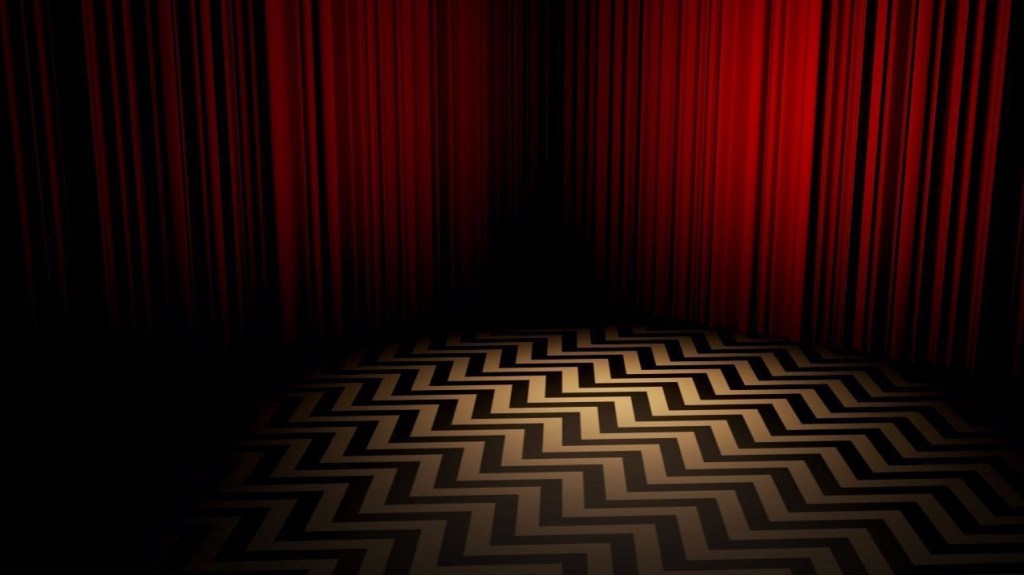

Last week I watched the first season of “Twin Peaks,” early 90’s harbinger of prestige television and brainchild of enigmatic auteur David Lynch. This is a show that watches itself alongside you, not while winking and nudging, but in such a way that you can tell when it laughs, cries, or leans in. It’s a show in which the idea of a mystery comes to matter much more than its resolution. It’s a show that’s completely Lynchian.

Lynch has a tendency to leave the keys to his work lying about for viewers to find. In “Blue Velvet” it’s the opening montage, which suggests that ‘small town USA’ has dark secrets suppressed below its shimmery surface. In “Mulholland Drive” it’s a literal key that is discovered in the latter-half of the film, one that has the power to unlock every single one of its illusive layers at once. In “Twin Peaks” Lynch has sprinkled small clips of a soap opera called “Invitation to Love” throughout the show. For the viewer, it connects the worlds on the inside and outside of their TV screen (a device seen recently in the Coens’ “Hail, Caesar!”, a movie that turns to Lynch’s toolbox on more than a few occasions), and it works to normalize the show’s heightened emotional displays that may initially act as a barrier to entry for viewers unfamiliar with Lynch.

Much like “Invitation to Love,” the most attractive force at play in the world of “Twin Peaks” isn’t the melodramatic narrative, but the brazenness with which human emotions are painted (and, in some cases, splattered abstractly) across the canvas of the screen. It’s jarring at first to see, as the performances feel like the actors are playing to cheap seats that don’t actually exist. All of this isn’t to say that the melodrama is ineffective or good only for the purpose of parody, for in practice it works so well that it can make you wonder why all television hasn’t resorted to being this startlingly on-the-nose about the emotional states of its characters.

The answer in this case is that the efficacy here stems from the intuition of the artist. (This is, after all, the same man who crafted and scrambled a sitcom involving three anthropomorphic rabbits into a series of vignettes which were equal parts unsettling and captivating, vaguely familiar and yet utterly unique.) Lynch has seemingly found a way to distill the ingredients of film to their most basic elements and is experimenting with new ways to combine them before our eyes and ears, provoking the gamut of human reaction in response. In a Lynchian world, something banal can be portrayed as sinister just as easily as it can be overlooked entirely; the dividing line is drawn by the hand of the artist (which is about as far from invisible as it gets).

Any world in which you can essentially see the artist at work is imbued with a greater degree of immediate artificiality than one in which the hand is disguised. There are great works of art that subdue this fact, but there are none that escape it. The artificiality of Lynch’s worlds isn’t the point of it all, but it is essential to the point. He plays on the extremes of the medium, creating works that threaten to burst from the screen and spill into reality. There are shots where the images are so grainy that you can almost count the individual imperfections. This is doubtlessly an alluring quality to Lynch, and its use as a tool is epitomized in his move to digital to film “Inland Empire.” Some things may be lost in the distortion that dances across the images on screen, but a new, imposing, and previously unseen life emerges.

The sound of “Twin Peaks” is just as iconic as its visuals. Angelo Badalamenti’s score is comprised of recurring themes that tie everything together. In a town where there are no strangers, of course each song in the soundtrack is as familiar as a next-door neighbor. Repetitive but never tiresome, it takes on a new life in every scene that it underscores.

When viewers are lured into worlds nested within the uncanny valley, they open their minds to new possibilities and the surreal becomes palatable. Lynch’s fascination with the subconscious has yielded a series that plays out like one big dream shared by every person that engages with the work.

“Twin Peaks” makes its return on May 21st. It’ll be available on Showtime.

If any of this has piqued your curiosity, check out David Foster Wallace’s brilliant exploration of what it means for something to be Lynchian, “David Lynch Keeps His Head.”

If you haven’t seen “Mulholland Drive,” watch it tonight! If you have, then read through Film Crit Hulk’s definitive guide to the film, “Hulk vs. The Genius of Mulholland Drive,” and then watch it again.

Leave a comment